By Michael Driskill, MƒA Chief Operating Officer

At MƒA, we believe that the best way to improve education is to get expert teachers together. We think that when teachers share good ideas with one another both they and their students benefit.

We think that when teachers share good ideas with one another both they and their students benefit. But sharing good ideas about teaching is harder than it sounds. Teachers - especially in New York City - have to communicate across many differences. Fortunately, there is a common language that can help.

The challenge in communicating across differences

In August I facilitated an orientation workshop for about 300 teachers who were recently accepted to MƒA. About half were new to the organization, and the others were entering either their second, third, fourth or even fifth fellowship. The teachers attending represented every borough, every grade K-12, and every subject in STEM.

I started the workshop by asking them: If you had to pick just one thing that matters most in teaching, what would it be? I asked everyone to type their answer in the chat (orientation was on Zoom), which soon flooded with responses.

There were similarities and differences in what the teachers wrote in the chat. “Equity,” was a popular choice, as was “engagement.” Some teachers mentioned particular teaching methods, like “problem-based learning,” and others pointed to more abstract teaching goals such as “rigorous content.” As a group, we seemed mostly on the same page, but it also wasn’t clear the extent to which we were talking about the same things. What did different teachers mean when we said teaching needs to be “equitable,” or address “rigorous content?” Did a third-grade teacher working in the Bronx mean something different from a high school teacher working in Manhattan? Problem-based teaching is a means, but to what end? Was there anything missing from our list? How would we know?

We followed this activity by watching video excerpts from lessons taught by different teachers working in various schools. The first was a high school math lesson on angles. The second was a middle school biology lesson on the circulatory system. The third was an elementary lesson on decimals, fractions, and percent. The videos weren’t examples of perfect teaching, they were daily lessons made public by brave teachers willing to open their classrooms to others. After watching each video, I put participants into breakout rooms and asked them to talk about what they noticed and make notes of the most important things they saw, focusing especially on what they thought the experience was like from the point of view of students. I joined some of the breakout rooms to listen in. Again, there seemed to be general agreement but it wasn’t clear the extent to which teachers were talking about the same things.

The five things that matter in teaching

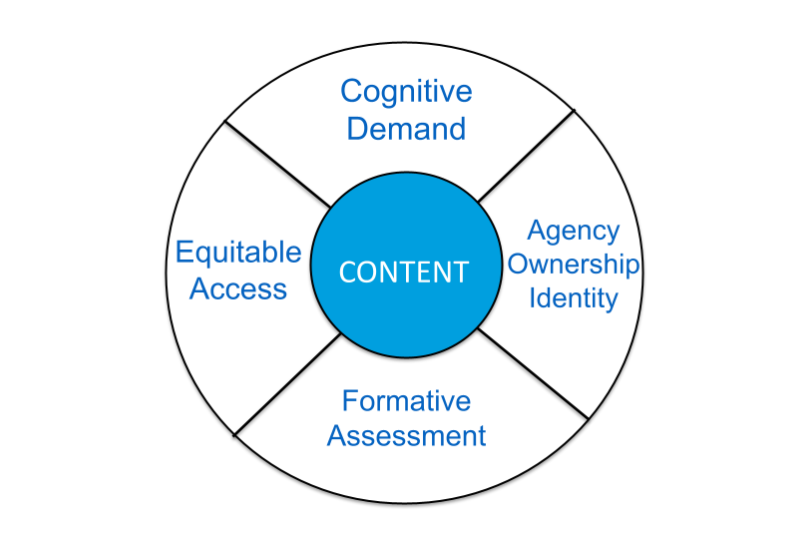

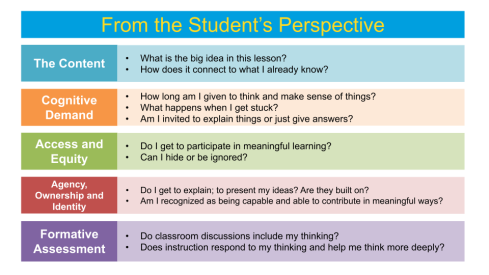

When we returned as a whole group, I made a claim: there are only five things that matter in teaching. I proposed that anything they noticed as important in the videos could be sorted into five dimensions of teaching, defined by some key questions from a student’s perspective:

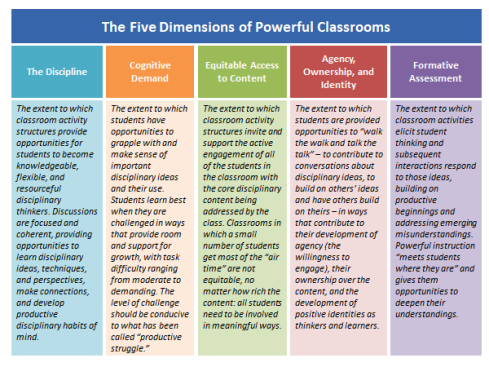

To test the claim, participants returned to their groups and entered their observations into five columns in a shared Google Sheet, with each column representing one of the five dimensions as illustrated in the diagram below. I switched things up, with the description of each dimension now described from a teacher’s perspective:

The spreadsheet soon filled with interesting observations about the lessons. And while I had provided a sixth column for observations that didn’t fit, it remained mostly empty, with the notable exception of some observations that fit within more than one column.

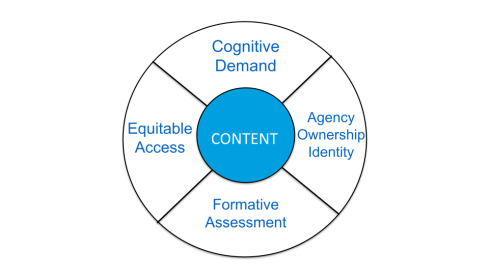

When everyone reconvened, I acknowledged that observations could fit within more than one category, and shared a final nonlinear viewpoint of to illustrate:

From this viewpoint, core disciplinary ideas and habits of mind are central to teaching. But content alone is not enough. For all students to be really learning, the other four dimensions must be also present. Sometimes it’s helpful to reduce the complexity of a situation by focusing on just one area; other times it’s helpful to think about the overlap.

Using the TRU Framework

This five-dimensional framework for teaching is called Teaching for Robust Understanding (TRU). It was developed over the last decade by researchers at the University of California Berkeley seeking to understand the dimensions of teaching that are necessary and sufficient for students to emerge as “knowledgeable, resourceful, flexible thinkers and problem-solvers.” I would add “empowered” to the list, in light of TRU’s focus on agency, ownership, and identity. I am certain that every MƒA teacher aims to help students develop these characteristics. The value of TRU is that it provides a common language to sharpen our conversations about teaching, especially when we communicate across differences.

Our concluding whole-group conversation at orientation proved that point. Teachers discussed strengths and areas for improvement in the lessons they saw, using the language from TRU to justify their claims. As we talked, I was reminded of how complex teaching is, and how much there is to think about in just a few minutes of classroom video.

TRU at MƒA

At MƒA we’ve been using TRU with small groups of teachers over the past few years, and it’s been very popular. It’s a good fit for the teachers in our fellowship since it provides an accessible language that supports conversations about teaching, without telling them how to teach. It was developed to support collegial investigations of teaching, and not to evaluate teachers. We’ve decided to make TRU available to all MƒA teachers now, adopting it as the common language for our entire fellowship program. We’ll try to do this the MƒA way, without being heavy handed or bureaucratic, positioning TRU as a resource but not a mandate. We want teachers to use it because they think it’s useful, not because we told them they should. It takes time to learn any new language, and incorporating TRU into our work at MƒA is a long-term goal.

I’m excited to see what our teachers do with it. Alan Schoenfeld, the primary author of TRU, often says that in a sense, it’s “nothing new.” I agree: expert teachers have always known what we should talk about when we talk about teaching. But when we talk about the same things in different ways, we can miss important opportunities to learn from one another. I believe that incorporating TRU will simply enhance the ability of the expert teachers at MƒA to spread good ideas about teaching in NYC and beyond.