How MƒA motivated Erica Tunick to focus on cognitive demand in her classroom, offering an inside look into how her students were thinking.

In the spring of 2022, MƒA Master Teacher Erica Tunick was looking for a way to get her students off their computers and challenge them to be more self-directed with their learning. While Tunick was an experienced teacher, the 2019-20 school year had been her first teaching 7th grade science at Forte Preparatory Academy Charter School, and the switch to remote learning during the COVID-19 pandemic had put a lot of limitations on her still-developing curriculum.

“It was very passive, and there weren't as many opportunities for me to elicit student ideas or have students engaging in collaborative conversation that would lead to problem solving or finding answers,” Tunick recalls.

That spring, Tunick participated in a Professional Learning Team (PLT) through MƒA called “Diving into Teaching for Robust Understanding.” During one session, she jumped at the chance to bring a sample assignment to the group, and get their feedback on how to increase cognitive demand for that assignment. One of five dimensions in the Teaching for Robust Understanding (TRU) framework developed over the last decade by researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, cognitive demand is the level and complexity of thinking required of students in order to engage with and complete a task.

Tunick’s sample assignment, from her astronomy unit, was to look at a model or a diagram of an eclipse and determine whether it was a solar or lunar eclipse. “It's absolutely aligned to what kids need to know, but it's very straightforward,” Tunick says of the exercise. “They either get it right or wrong, and there's very little way for me to see the thinking going on behind this question.”

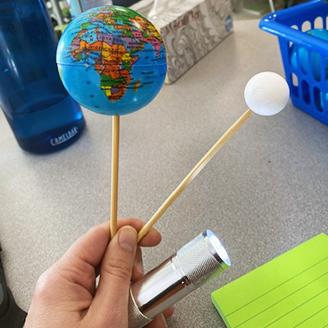

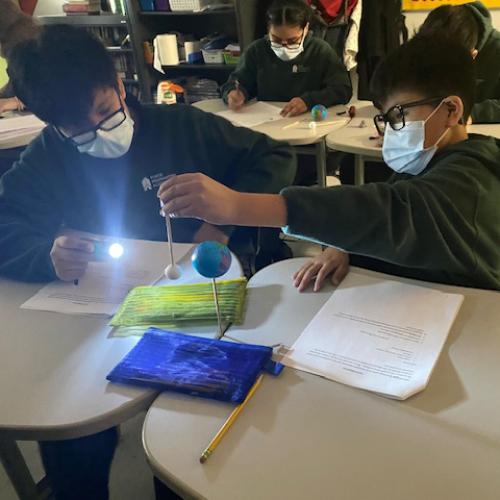

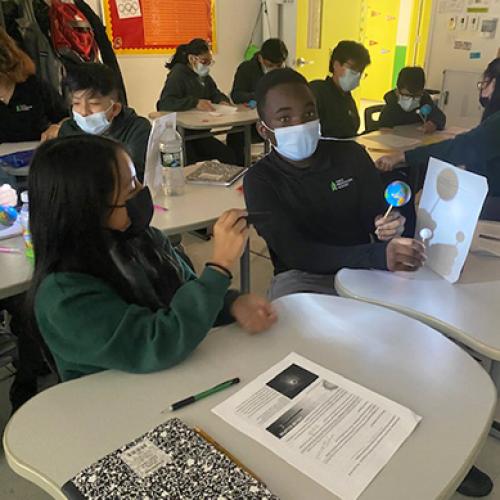

With feedback from her MƒA colleagues in the PLT, including not just fellow middle school science teachers but elementary and high school science and math teachers, Tunick was able to develop a task that served the same purpose, but greatly increased the cognitive demand for her students. Rather than simply look at a diagram, students would be given materials — a small globe, a styrofoam ball representing the moon and a flashlight that stood in for the sun — and asked to create both solar and lunar eclipses.

“We basically transformed it into students developing an explanatory model where they are given tools and they have to use those tools,” Tunick says. “It was really exciting to have, in this very short period of time, all these great ideas and thoughtful questions being posed, and to make what I was putting in front of my students so much better.”

Back in her classroom, Tunick saw the impact of the new eclipse assignment immediately. “Class ended, and I had so much data about how much my students knew, and what the remaining gaps were,” she recalls. “Through all the thinking steps and recording and making decisions, I get a window into how the kids are thinking and can respond to that thinking to make sure they've mastered the content and have a strategy going forward.”

The feedback she received in the PLT serves as Tunick’s inspiration whenever she needs to increase the level of cognitive demand for her students for a given assignment or task. She has not only channeled the experience into the planning of professional development sessions for her colleagues in the science department, but has made use of the TRU framework to give more direct feedback to fellow teachers on individual lessons and planning.

One of five dimensions in the TRU framework, cognitive demand is the level and complexity of thinking required of students in order to engage with and complete a task.

With feedback from her MƒA colleagues, Tunick was able to develop a task for her astronomy unit that greatly increased the cognitive demand for her students.

Rather than simply look at a diagram, students are given materials — a small globe, a styrofoam ball. a flashlight — and asked to create both solar and lunar eclipses.

“I like the framework because it takes what can feel like 900 boxes on a rubric and boils it down into five ideas,” Tunick says. “It makes trying to improve someone's [teaching] practice much more accessible and easier to manage.”

Tunick has also used the TRU framework to guide conversations with her colleagues about other dimensions of teaching, including increasing student agency and ownership of their work in the classroom. “If kids are thinking, they are driving the direction of class, they’re becoming confident, and they're going to be mastering the content,” she says.

Beyond her experience with the TRU PLT, Tunick credits MƒA and her fellow Master Teachers for ongoing support and resources more generally, whether it’s learning more about new state-wide testing requirements or getting ideas for how she can be a better leader and mentor within her school community. “To say teaching is challenging is an understatement,” Tunick says. “Being a part of the MƒA community, participating in collaborative courses, and learning new things helps keep you motivated.”

Tunick has not only channeled the experience into the planning of professional development sessions for her colleagues in the science department, but has made use of the TRU framework to give more direct feedback to fellow teachers on individual lessons and planning.